[tab_nav type=”two-up”][tab_nav_item title=”Clinical Case” active=”true”][tab_nav_item title=”Answer” active=””][/tab_nav][tabs][tab active=”true”]You are working late one night when you are called by the ED to come down and help with someone who needs direct admission to the ICU. As you walk into the department you realize that it is a REALLY slow night, so you wonder what they might want you for. You grab the chart and see:

“59 yo F with a PMHx of HTN, TIAs, s/p L CEA transferred from an OSH with a L parietal ICH”…..

While the transport service gets the patient unbuckled and onto a bed you see the transport nurse and try to get some history. Apparently the patient had a “massive migraine” at home, then was unable to move her right arm or right hand. EMS was called and, when they arrived, she had developed facial droop and slurred speech. The outside hospital gave the patient an NIH stroke scale of 6. During her ED stay there the patient degraded to a GCS of 7 and she was intubated. A CT scan showed a L parietal ICH with 4mm shift.

You thank her and enter the room to see an awake woman, arousable with 5/5 strength on the left side, but densely plegic on the right. Pt has right facial droop, but follows commands.

The patient is admitted to the Neuro ICU, has a follow-up CTA/V showing no change to the size of the ICH. You do a cardiac assessment on arrival to the ICU and find an EF of 25%:

Apical 4-chamber view:

Short Axis:

This is very unexpected as the patient has no cardiac disease in her history. A bedside CXR shows massive flash pulmonary edema and lab work shows a troponin of 1.52 (?!? also very unexpected)… You start the patient on dobutamine and a lasix drip for presumed cardiogenic shock and heart failure.

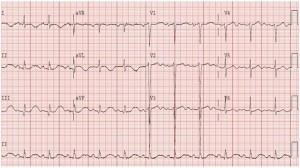

Her EKG:

So what is going on here? Is the heart failure a “red herring” or a reaction to the head bleed? What do you have to watch out for?….. [/tab]

[tab]

Answer:

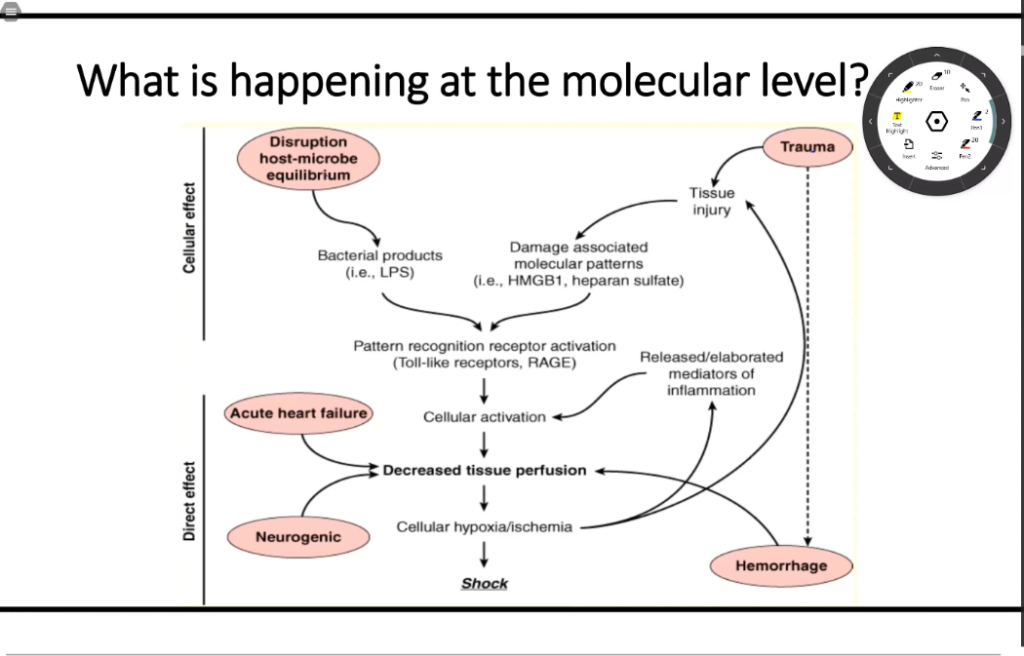

Brain Heart Syndrome

- Dates back to 1942: “Voodoo Death” by Walter Cannon: “Death caused by a

lasting and intense action of the sympathico-adrenal system” - Abnormalities including: EKG changes, cardiac arrhythmias and myocardial dysfunction/stress-induced cardiomyopathy.

EKG Changes associated with Intracranial Disease:

- SAH: marked QT-prolongation, with large T-waves and U-waves

- Ischemic CVA: large septal inverted T-waves, prolonged QT intervals, and large U-waves

- Treatment: supportive, with avoidance of QT prolonging agents + K supplementation to avoid further U-Waves

- Monitoring: Continuous EKG telemetry is advised with admission

- Prognosis: minor EKG changes can resolve over days to months with little no sequelae

- Studies show that the combination of Q-waves, ST-depression, and inverted T-waves predicts mortality and adverse neurological outcomes

Arrhythmias:

- Incidence: 20-40% of patients with ischemic CVA, and 100% of pts with SAH

- PVCs are most frequent (53%), followed by asystole, sinus brady, A fib, SVT

- Treatment: mainly supportive

- Life threatening arrhythmias: ACLS protocol, electrolyte corrections (K), and avoidance of QT prolongation (such as Lidocaine or Amiodarone)

Myocardial dysfunction:

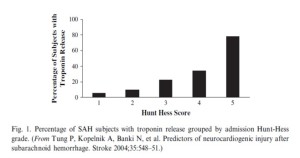

- SAH induced cardiac dysfunction is a well-studied model of neurocardiogenic injury

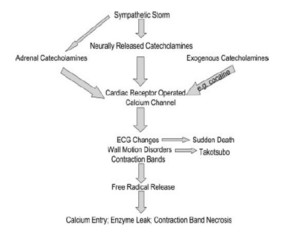

- Pathophysiology: excessive sympathetic stimulation causing subendocardial lesions, aka: contraction band necrosis

- Occurs in the vicinity of the cardiac nerves and not in the macrovascular distribution

- There is a correlation between size of SAH and cardiac injury

- Prognosis:

- Troponin elevation: associated with an increased risk of cardiac complications, death or poor functional outcome at discharge

- Elevated BNP levels: associated with delayed neurologic deficits and predict the 2-week GCS score

- Elevated troponin and BNP levels: independent and strong predictors of inpatient mortality after SAH

- Mechanism proposed by Samuels, et al:

- Treatment:

- Beta blockade: reduce myocardial dysfunction, limited use with cardiogenic shock

- Standard CHF support: ACEI, diuretics, mechanical support (when needed)

- Anticoagulation: reduce risk of LV mural thrombus in apical involvement

- Prognosis:

- LVEF recovery takes 1-4 weeks

BACK TO OUR PATIENT:

Neuro exam gradually improved and the patients started following commands with improving right hemiparesis. Cardiogenic shock gradually improved and support was weaned off. Home HTN meds were resumed with the addition of Metoprolol.

Repeat Echo showed following:

[/tab][/tabs]