Today is quite a pleasure and a unique opportunity for MCCP, this talk was sent to us by Andrew Lim, MD. During his tenure as a medical student at UCSF Dr. Lim found time to also complete the UC Berkeley – UCSF Joint Medical Program for his M.S. in Public Health. Andrew put these skills to good use as an Emergency Medicine resident at The University of Washington jumping on every chance to make his mark on the International Health community. However, don’t let the ACGME status fool you, he has been around the world working with some remarkable people along the way. The things you will hear and learn in this talk will open your eyes to just what it means to treat sepsis in Sub-Saharan Africa, or how to make an ARDS diagnosis when a blood gas is a luxury. I assure you, this is one the better uses of 30 minutes you will find all year!

PS: This talk is just a taste of what UWashington.CCProject.com is destined to be!

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Clinical Pearls (Outline provided by Dr. Andrew Lim)

- Global health and critical care can be united because:

- “At its core, critical care is simply healthcare for very sick patients”… “The care of the critically ill patient is a global enterprise.” (Elizabeth Riviello, MD)

- Three major pillars:

- The timely recognition and stabilization of critical illness

- Access to and delivery of critical care

- The definitive management, recovery, and rehabilitation of the critically ill

- Global critical care is applying these foundations of critical care to areas of the world without the resources we are accustomed to.

- Recognizing the extent of critical illness where complex monitoring doesn’t exist.

- The industrialization and evolution of Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) is rapidly changing:

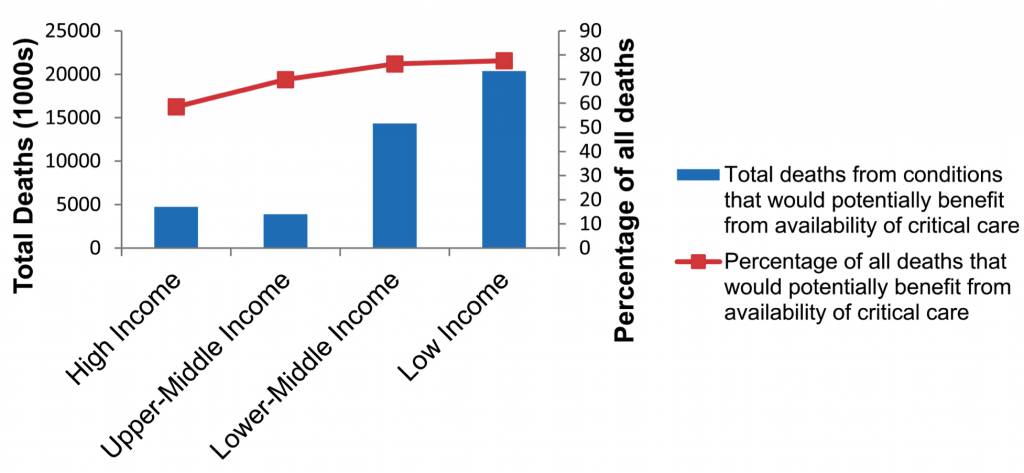

- A disproportionate amount of the critically ill are in LMIC, where there is poor access to and development of critical care resources. (ATS 2013)

- There is increased transmission of communicable diseases, with a staggering rate of deaths from sepsis – world rates about 5x that of High Income Countries (HICs), and rates in Sub-saharan Africa about 12x that of HICs. (Lancet 2010)

- There is a false assumption that these countries do not have the resources to perform critical care.

- The industrialization and evolution of Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) is rapidly changing:

- Recognizing the extent of critical illness where complex monitoring doesn’t exist.

- Four components to the strengthening of critical care systems in the developing world:

- Addressing Local Context and Population:

- The building of any critical care response system must take into account contextual factors, such as local politics, economics, and history.

- Management of Limited Resources:

- Huge disparity of MDs, nurses, and other healthcare providers between HICs and LMICs. (NEJM 2014)

- Inadequate critical training of doctors and nurses in the clinical management of critical medical conditions

- Sepsis representing the largest knowledge gap.

- Difficulty in accessing a variety of ICU equipment, monitors, medicines, and blood products in LMICs compared to HIC counterparts. (J Intensive Care 2015)

- There is a direct and positive relation between the amount of ICU capacity and healthcare dollars spent per capita. (PLoS One 2015)

- Bosnian study showed that ICU care was ”very cost effective” compared to similar patients in other settings receiving floor care only. (World J Crit Care Med 2016)

- Regionally Focused Research:

- A one-size-fits all approach to critical care based on high income country research can fail in resource-limited settings.

- Some examples where HIC research and assumptions fail in LMIC:

- FEAST Trial: a multi-center RCT looking at mortality amongst pediatric populations with signs of sepsis comparing the effects of fluid boluses.

- There was no significant impact between colloid or crystalloid boluses.

- Giving resuscitative fluids was more harmful than a fluid restrictive approach overall.

- The Kigali Modification of the Berlin criteria: utilized several individually validated replacements of the key Berlin criteria such as ultrasound and pulse oxygen sat/FiO2 ratio.

- Identified a 4% prevalence of ARDS where 0% fit Berlin criteria.

- Example that critical illness and critical care should be defined by the gravity of illness of a patient rather than the diagnostic and treatment modalities available.

- FEAST Trial: a multi-center RCT looking at mortality amongst pediatric populations with signs of sepsis comparing the effects of fluid boluses.

- National & International Surveillance:

- The scaling up and unifying of broadscale interventions.

- Requires the cooperation of national + international actors to create guidelines and best practice recommendations.

- Simultaneously, we must allow for regional tailoring of interventions based on local research.

- Involves national health ministries, university hospitals, district police, fire response systems, and public infrastructure departments.

- Examples:

- WHO interventions such as Trauma Care Checklist

- Emergency Care Systems Framework (WHO Emergency, Trauma, and Acute Care Programme)

- World Bank data on nosocomial surveillance

- The scaling up and unifying of broadscale interventions.

- Addressing Local Context and Population:

- In conclusion, Global Critical Care is without a doubt an essential field, as health systems must respond to the increasingly complex health needs of the developing world.

Suggested Reading

- Murthy S, Adhikari NK. Global health care of the critically ill in low-resource settings. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013 Oct;10(5):509-13.[Pubmed Link]

- Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet. 2010 Oct 16;376(9749):1339-46. [Pubmed Link]

- Crisp N, Chen L. Global supply of health professionals. N Engl J Med. 2014 Mar 6;370(10):950-7. [Pubmed Link]

- Tripathi S, Kaur H, Kashyap R, Dong Y, Gajic O, Murthy S. A survey on the resources and practices in pediatric critical care of resource-rich and resource-limited countries. J Intensive Care. 2015; 3: 40. [Pubmed Link]

- Murthy S, Leligdowicz A, Adhikari NK. Intensive care unit capacity in low-income countries: A systematic review. PLoS One 2015;10(1):e0116949. [Pubmed Link]

- Cubro H, Somun-Kapetanovic R, Thiery G, Talmor D, Gajic O. Cost effectiveness of intensive care in a low resource setting: A prospective cohort of medical critically ill patients. World J Crit Care Med 2016, May 4;5(2):150-64. [Pubmed Link]

- Maitland K, Kiguli S, Opoka RO, Engoru C, Olupot-Olupot P, Akech SO, et al. Mortality after fluid bolus in african children with severe infection. N Engl J Med 2011, May 26;364(26):2483-95. [Pubmed Link]

- Riviello ED, Kiviri W, Twagirumugabe T, Mueller A, Banner-Goodspeed VM, Officer L, et al. Hospital incidence and outcomes of the acute respiratory distress syndrome using the kigali modification of the berlin definition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016, Jan 1;193(1):52-9. [Pubmed Link]